CS 184: COMPUTER GRAPHICS

PREVIOUS

< - - - - > CS

184 HOME < - - - - > CURRENT

< - - - - > NEXT

Lecture #18 -- Mo: 10/28, 2002.

NOTE: October 30 deadline for (written)

requests to do a different final project.

Review: Lights and Color

The color of lights or of object surfaces is represented with 3 components

R,G,B.

This works because the human visual system has three types of

color receptors.

Review of important

directions and unit vectors: L, V, N, R.

Preview of all the coefficients that you will see shortly: C's and

K's

Types of Light

Sources in SLIDE:

Ambient, Directional, Point, and Spot Light.

Superposition Law:

Calculate the effects of each light individually and sum all the resulting

effects.

(I.e., there is no interactions between photons).

Lighting /(Surface) Models

Illumination (Lighting / Surface) models:

They tell us what brightness and what color to expect

(physically) at a surface point.

1. Lambert Surfaces

This is an idealization of diffusely reflecting (chalky)

surfaces.

Their main advantage is that the apparent brightness of any

spot on the surface is viewer-independent.

LAMBERT SURFACES -- what we see:.

Formula that shows view-angle independence.

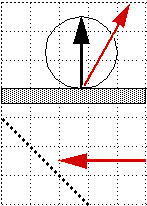

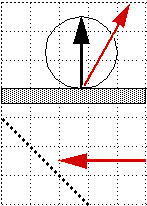

LAMBERT PHYSICS -- why that is so:

Show where the cosine factors are coming from and why they cancel:

All the lighting energy that hits the surface gets absorbed temporarily,

then some percentage gets reemitted with some broad distribution

and which has a maximum re-emision probability perpendicular to surface.

Light absorption falls off with the cosine of the angle between

light and face normal.

This is because a surface at a non-perpendicular angle in a flux of

photons captures fewer

photons (by a cos- factor), since it exposes a smaller cross sectional

area to the photon stream.

This effect is viewer independent and can be pre-calculated once at

scene construction time.

The percentage of light re-emitted in a particular direction

depends on the properties of the surface, e.g., Kd, Cd

{R,G,B}

Light emission and (diffuse) reflection (= re-emission) are both

strongest in the normal direction;

they fall off with the cos of the angle away from the normal (the reason

is that grazing photons

have a hard time escaping the "rugged" surface, i.e., they get trapped

again by protrusions).

.

.

When viewing a surface from an arbitrary angle, this fall-off

is compensated by the fact that,

as we see the surface more foreshortened, we also crowd more emission

centers into

the apparent solid angle of our viewing field by 1/cos . ( DEMO

with black page with white dots.)

Thus a chalky Lambert surface has an apparent brightness

that does not vary with view direction.

This also explains why the apparent intensity of the sun is constant

across the whole perceived "disk".

(The sun is a " Lambert type emitter").

Key Point:

Flat polygons will appear of uniform brightness when uniformly lit,

and have the same brightness from all view points !

Thus the output spans for a flat polygon can be of uniform brightness

from left to right edge.

2. Perfect Mirrors

Shiny surface with complete specular reflection.

Reflection laws: L, N, R in same plane; incident angle = reflection

angle (against normal),

but R is on the other side of the normal vector.

The result is, that we see a bright reflection spot where

the camera lies in the R direction;

everywhere else the surface is dark !

3. Phong Approximation of Real Surfaces

Real surfaces are a mixture of chalky properties and of a dull, dusty mirror.

==> They have some diffuse as well as some specular reflection.

The reflected beam is spread out in a small angle around the unit vector

R.

==> Phong model: Models the reflective component on a real surface

as a "club" shape around R

Its intensity falls of with a user definable power of the cosine of

the deviation angle from the ideal R direction.

Phong Illumination/Lighting/Surface Model:

Show effect of exponent of cosine function.

Phong Highlight on glossy surface:

Even uniform directional light falling on a flat surface can produce

non-uniform brightntess,

if surface is partially reflective and we use a Phong illumination

model.

4. Better Approximations of Real Surfaces:

Real materials are more complicated: Spreading of light (Phong

exponent) may depend on:

-- the incident angle {Torrence Sparrow model }.

-- the color of the light {spectral behavior; different

wavelenghts get absorbed/reflected differently.

-- the surface material:

-> in metal, reflected

light penetrates deeper into substrate, picks up color of metal {metalness

factor};

-> on plastics, the

light bounces off a surface layer, and keeps more of its own color composition.

Surface Characterization

Relationship

between ka, kd, ks; and the C’s and the K’s

Shading

Examples using spheres.

Brightness Normalization.

Normally one tries to carefully choose lights so that the produced brightnesses

fall into the range 0 to 1.0,

which is then mapped onto the, say, 256 discrete beam intensities in

the CRT.

In spite of best intentions the sum of all calculated brightnesses

may exceed unity,

this may produce strange effects if left unchecked !

--> at the very least: clip to unity

--> better: detect this, and scale down all brightness

values on object or in whole scene.

Now that we know what the brightness is that we would like to represent,

the question arises, how can we efficiently generate all the pixels

of the right brightness ?

Shading and Rendering:

Techniques to produce desired display brightness -- efficiently !

We cannot afford to do a full shading calculation for each pixel.

Lambert lighting model + flat faces + uniform illumination -> easy:

==> ONE brightness value per polygon.

==> just take a representative value at centroid of face, and apply

brightness values to all pixels of the polygon.

All other cases are harder: they result in non-uniform apparent brightness!

Causes of non-uniform brightness:

-- Point light or spotlight close to surface.

-- Curved surface where incident angle of light

changes..

In both cases, one could sample more finely, and subdivide the surface

patch into many smaller pieces.

-- But this would still look patchy with sharp,

contrasty brightness boundaries in between.

We need to smoothly blend these patches together!

--> Sample illumination and calculate brightness

at corners of patches

and then interpolate between these sample points.

-- We can cast this procedure into the framework

of our scan-line algorithm,

and do an interpolation

similar to the interpolation of the z-values in the z-buffer.

1. Gouraud Shading Technique:

Linear interpolation of (scalar) brightness values

Good for: handling small nonuniformities in illumination intensity,

or for polyhedral approximations to round objects.

Principle: Use barycentric or bilinear (with sweep-line) intensity

interpolation;

==> Implementation:

GOURAUD

SHADING TECHNIQUE:

1. Compute shading at visual vertices, A, B, C, D ...

2. Compute shading along edges by linear interpolation between vertices.

3. Compute shading along spans by linear interpolation between edges.

Smooth shading can be applied whenever apparent brightness changes

across a surface,

-- either because the illumination is non-uniform,

-- the reflection has highlights,

-- or the surface is curved.

Faking smooth rounded objects:

Take an averaged brightness value at each corner,

derived from all incident lights and averaged vertex normals

(= vector sum of the face normals of all the adjacent polygons weighted

by angle subtended at vertex).

The result is fake: edges remain straight (visible at the silhouette

edges!) -- but it is efficient.

Limitations

of Gouraud Shading:

Some flat spots; extrema may be "short-circuited";

discontinuities at concave corners; missing highlights...

2nd Technique: Phong Shading:

Interpolate normal vector directions

We can fix some of the above problems with a more sophisticated interpolation

scheme.

PHONG

SHADING

1. Compute normals at visual vertices, A, B, C, D ...

2. Compute normals along edges by vector interpolation.

3. Compute normals along spans by vector interpolation.

4.For every pixel compute brightness from interpolated normal direction

and local light intensities.

Phong can interpolate over flat spots. -- But it is not perfect

either !

Limitations

of Phong Shading:

“Corrugated” structures with too few vertices (just a zig-zag)

may have all parallel normal directions and cannot represent periodic

shading variations.

Geometry that is not seen at vertices cannot be inferred !

Illumination changes that are not seen at vertices cannot be inferred

!

Reading Assignment:

Study: 2ndEd: Ch 6.1-6.5; Skim: 2ndEd: Ch 6.6-6.11.

Study: 3rdEd: Ch 6.1-6.5; Skim:

3ndEd: Ch 6.6-6.11.

New Homework Assignment:

ASG#8:

"Lighting

Calculations and Gouraud Shading"

This assignment can also be done with ANY

PARTNER

-- possibly the one with whom you might do

the final project.

PREVIOUS

< - - - - > CS

184 HOME < - - - - > CURRENT

< - - - - > NEXT

Page Editor: Carlo H. Séquin

.

.