The Anatomy Of

A Miracle

The wildest

kickoff return in history began when Kevin Moen of Cal fielded a

Stanford squib (below) and ended, five laterals and a felled

trombone player later, amid hysteria

BY RON FIMRITE

(Sports Illustrated, September 1, 1983, Vol. 59, No.

10, pp. 212-228; Illustrations by Bart Forbes)

© Copyright 1983, Sports

Illustrated

It is now called, simply, The Play.

There is no need for further explanation,

because there has never been anything in the history of college

football to equal it for sheer madness. You've seen The Play, of course. Anyone

who so much as glanced at football on

television in the final weeks of

last season must have seen it, for scarcely a college or professional

game was shown that did not feature The Play at halftime, usually to the musical accompaniment of the William

Tell Overture. But if

by some phenomenal oversight you did miss it, videotapes of it are available

from the University of California at $100 a pop. Within two months of The Play, the university had sold more than 250

tapes. For a lot

less—$6.50—you can buy a tape recording of announcer Joe Starkey's

hysterical account of The Play from San Francisco radio station

KGO. Within three weeks, more than 4,000 of

these tapes had been sold. T-shirts with a complex diagram of The Play,

marketed by Cal's Alpha Sigma Phi fraternity, are also available for $8. Some

20,000 of these had been sold by the end of

July. Glossy photographs of The Play can be purchased from the Oakland

Tribune for $5 apiece.

In short, The Play has become the basis of a sort of cottage industry.

<<Click

on pictures for larger, higher quality images>>

It all happened as the clock ran

out on the 85th Big Game between Cal and Stanford at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley

last

November 20 before many of the original crowd of 75,662. Stanford had gone ahead

20-19 on a 35-yard field goal

by Mark Harmon with four seconds to play. At that point the game was already

being acclaimed as the most thrilling in the

long history of this exciting rivalry. Even Cal supporters were prepared

to concede that they had witnessed a classic.

When Stanford kicked off after the field goal .

. . well, more about that later. For now,

it's enough to say that as The Play

unfolded, the players shared their turf with virtually the entire Stanford band, several Stanford cheerleaders,

assorted spectators, three

members of the Stanford Axe Committee—to the winner of the

Cal-Stanford game goes the Axe—who were holding aloft the victory

trophy on the Stanford 17-yard line, and at least 11 illegal players who had

wandered onto the field from the

benches of the teams. A trombone

player in the Stanford band would become as celebrated afterward as

any of the victorious athletes, and at one point Cal would have players named

Richard Rodgers and Gilbert and Sullivan on the field at once, only one of them

legally. "It appeared to me that the

weakest part of the Stanford defense was the woodwinds," said

spectator Ellen Edmondson afterward.

Actually, the band played only a minor note in an event that one Cal

player, Running Back John Tuggle, described as "an act of God."

Cal has an

honorable history of bizarre football plays. In the 1929 Rose Bowl game against Georgia Tech, Golden Bear Center Roy Riegels ran 69 yards in the wrong

direction with a recovered fumble, a

blunder that led to a safety and an

8-7 loss. In 1940, a Cal fan named Bud Brennan jumped out of his seat in the south end zone at Memorial

Stadium and tried to tackle

Michigan's Tommy Harmon near the goal line. And there was a beaut in 1945

against UCLA. Cal's Ed Welch picked up teammate Jack Lerond's blocked punt and headed

for the UCLA goal 66 yards downfield. Hemmed in on the UCLA 40, he lateraled to Lerond, who ran the rest of the way into the end zone for the winning

touchdown. Gems all, but none matched The Play. More important, none occurred

in the Big Game.

The Cal-Stanford rivalry is one of the oldest west of the Mississippi,

dating from 1892, a season when the student manager of the Stanford football

team was an engineering major named Herbert Hoover. The designation Big Game may seem a trifle pretentious to Easterners, or

even to partisans of USC and UCLA, but Cal and Stanford do have a

great deal of tradition going for them. Moreover, the series has been characterized to an extraordinary extent

by upsets and last-second victories. Forty games have been decided by seven points or fewer, and though Stanford leads

the series 40-35-10, it has scored only 26 more points than Cal in the 85

games.

The 1982 Big Game

was the fourth in a decade to be decided within the last two minutes and the third to be won

on the final play. In 1972, with three seconds left, Cal freshman Vince Ferragamo (yes, that one)

completed an eight-yard touchdown pass to Steve Sweeney for a 24-21 win, and in

1974, Stanford won 22-20 on Mike Langford's

50-yard field goal with no time

showing on the clock. Stanford won 27-24 in 1976 with a leisurely 1:31

remaining.

The favored team

in this rivalry generally stands on shaky turf.

In 1947, Cal came into the Big Game with an 8-1 record in its first season under Coach Pappy Waldorf. Stanford was 0-8 and had averaged fewer than seven points

a game. Only an 80-yard pass play from Jackie Jensen to injured Halfback Paul Keckley with slightly more than two

minutes remaining gave the Golden Bears a 21-18 victory. In 1941, Stanford's

second Wow Boy T-formation team, under Clark Shaughnessy, entered the

Big Game a prohibitive favorite over a Cal

team with a 3-5 record. Stanford, quarterbacked by Frankie Albert, was

6-2. A win over the Bears, coupled with an

Oregon State loss to Oregon, would send Stanford to the Rose Bowl for the

second straight year. Cal scored on its first play from scrimmage and

went on to win 16-0.

There was little to choose between the

teams in 1982. Cal, under

a rookie coach, Joe Kapp, was 6-4, Stanford 5-5. In four of its losses,

however, the Cardinal had been oh so close.

Arizona State won 21-17 in the final 11 seconds; San Jose State won 35-31 in the last five minutes;

UCLA squeaked by 38-35; and Arizona

scored 28 points in the last 12 minutes to win 41-27, after Stanford had

led 27-13. Stanford had also won a couple

of thrillers, upsetting Ohio State 23-20 with 34 seconds left and

beating Washington State 31-26 with 22 seconds to play. The Cardinal's most gratifying

victory had been over No. 2-ranked Washington on

Oct. 30. With that 43-21 upset and the big win over the Buckeyes, both on

national television, Stanford seemed assured, despite its five

losses, of an invitation to the Hall of Fame

Bowl. It was an exciting team offensively, and in John Elway it had a player many observers were calling

the best college quarterback ever. A

win over the Golden Bears would presumably still leave Elway in the

running for the Heisman Trophy, even with

his team's undistinguished record.

Stanford was a seven-point favorite over a Cal team that had been

brutally beaten by USC (42-0), Washington (50-7), Arizona State (15-0) and UCLA

(47-31). The Bears expected no bowl bids.

Still, Kapp, who had never coached

at any level, was assured a

winning season, refuting criticism, much of it from fellow coaches, that he had no business in a job

for which he was so manifestly unqualified. The old Minnesota Viking quarterback did have some problems early

on—three assistant coaches quit, and Gale Gilbert, who was to

start at quarterback, threatened

to—but Kapp grew in office, as the old expression goes, and after his

team opened with two victories, the

question of his qualifications seemed moot. And his zeal was infectious. Kapp is fond of uttering ringing bromides—"One hundred [per cent] for 60

[minutes]"; "The Bear will

not quit, the Bear will not die"—as if they revealed truth.

Although some of his bombast more amused than aroused the relatively

sophisticated Berkeley students, he did

successfully drum into his players the conviction that the game is not over until the final gun. In the 85th

Big Game, this became a crucial advantage.

Kapp also insisted that playing

football at Cal should be fun.

He introduced a game played in Sunday workouts called, euphemistically,

"garbazz" (pronounced gar-bahz). "It's Mexican-French for

grab-ass, naturally," says Kapp. "We used to play it when I was with

the Vikings. It's a mixture of

basketball and football with elements of rugby. You just work the ball

downfield by passing it back and forth. Any

pass can be a forward pass. There are no offsides. When the ball is dropped the next play starts from

there. We do it on the day after a game just to break a sweat. It's the

only day we have to relax and have some fun. We have to meet and look at film and get ready for the next week,

but there's no reason we can't have a little fun while we're at

it." He could not have predicted that the climactic play of the Big Game

would, in effect, be a variation of garbazz.

Like Kapp, Stanford Coach Paul Wiggin had returned to his alma mater, where, again like Kapp, he had

been an All-America. Unlike Kapp, however,

he had extensive coaching experience:

nine years as an NFL assistant and 2Y2 seasons as head coach of the

Kansas City Chiefs. This was his third year as Stanford's coach, and for him it

had been a frustrating and worrisome one. The defense he had

promised to shore up after a disappointing

4-7 record in 1981 had failed him

again in the close losses, and his critics in the press and among alumni were becoming increasingly agitated.

If Wiggin couldn't win with the best quarterback in the history of college football, it was asked, what will happen

after Elway's graduation? Only Wiggin's strong Stanford ties had kept him on the job, but even they would not be enough

to save him if he lost the Big Game.

Wiggin is a true stalwart, a dignified man, forthright, friendly and

knowledgeable, but by the end of the season, the

criticism and the narrow defeats were beginning to wear on him. The win

over Washington had given him national recognition, but the heartbreaking

losses to Arizona and UCLA that followed had

brought him under merciless scrutiny once more. He would—some

say miraculously—survive what happened in the Cal game, but the

bitterness of this final fantastic defeat

would not leave him. "Ask me 10 years from now," he said two

months after The Play, "and I'll say the same thing—we won that

game." Wiggin got to keep his job, but

lost, it would appear, his sense of humor.

He and Stanford would be undone by four players whose careers until the

Big Game had been largely unremarkable. Kevin Moen and Mariet Ford, both seniors, were playing

in their

last college game. Moen, blond, blue-eyed, with a sparse mustache,

is the son of a Southern California banker.

He shared playing time at strong safety with Richard Rodgers,

another member of The Play's now famous foursome. Significantly, both Moen and Rodgers, who were close friends and roommates on road trips, had been

option quarterbacks in high school. Before The Play, Moen, who stands 6' 1" and weighs 190 pounds, had been known

chiefly as a hard tackler, The Undertaker of the Golden Bears secondary,

"a killer," says Kapp. Away from football, he seems introspective

and has a wry approach to life's complexities. Moen hopes to enter graduate school next spring in preparation

for a career as a teacher.

Ford was

easily the best known of the quartet. Though only

5' 9", 165 pounds, in two varsity seasons as a wide receiver

he caught at least one pass in every game he played and was outstanding as a kick returner. In his junior year he led all

Pac-10 wide receivers, with 45 catches. Last season he caught 42 passes for 568 yards, including seven

for 132 in the Big Game. His

astonishing one-handed 29-yard touchdown reception in the second quarter

might well have been the play of the Big Game, had it not been for The Play. Ford

majored in sociology and

is planning a career as a child psychologist. He is bright, affable and

hard-working. He made only one promise to his parents, he says, and that was to

graduate from Cal. He kept it.

Rodgers, a thick-muscled, 6-foot 200-pounder, is an exceptionally smart and disciplined player who, like

his friend Moen, is a fierce tackler. But his attitude is what sets him apart in the eyes of his coach. Rodgers, who's now

a senior, has an uncommon zest for

football, and is an unflinching optimist. "Richard plays this

game with a smile," says Kapp. Rodgers,

whose mother is a dispatcher for the San Francisco Police Department, is planning to attend law

school. Running Back Dwight Garner is the baby of the four. Only a freshman last fall, he played sparingly,

rushing only 30 times for 103 yards.

At 5' 9", 185 pounds, he is a darting, elusive runner and a capable pass receiver. His part in The Play

will be the source of endless controversy, a circumstance he finds somewhat daunting. "It's all a little hard for me

to handle," he says, "but I suppose I'll be thought of as

controversial from now on."

Neither

team scored in the first quarter of the game. In the second quarter Joe Cooper

booted a 31-yard field goal and Ford made his diving end-zone grab to give Cal

a 10-0 lead at halftime. Stanford pulled ahead 14-10 in the third quarter on

two Elway touchdown passes to Halfback Vincent White. A Cooper field goal

early in the fourth quarter made the score

14-13, and then, with 11:24 to go, Cal's Wes Howell made a sprawling touchdown catch that was fully as remarkable

as Ford's. Cal's try for a two-point conversion failed, so the score remained 19-14.

With 5:32 to play Stanford's Harmon kicked a field goal to make it 19-17. With 1:27 left and the ball on

the Cardinal 20, Stanford got the

ball for the last time. The huge crowd, sensing some final Elway heroics, stood

as one, animated, depending on school

loyalties, by hope or fear. On the west side of the 60-year-old stadium,

where Cardinal partisans held forth, the din

was nearly unbearable. On the east, Cal rooters nervously urged their team to hang on one last time. The sun was sinking beyond the rim of the stadium

as Elway set out to crown his

splendid career in the bedlam of Strawberry Canyon. His first pass, a swing to White coming out of the backfield, lost seven yards when White,

avoiding a tack‑ le, slipped on a field still damp from week-long rains.

Elway then missed his next two

throws, one spectacularly batted away from Wide Receiver Emile Harry by

Rodgers. Stanford now faced fourth and

17 on its own 13 with only 53 seconds remaining. Cal seemed a

certain winner. But Elway, ever unflappable,

zipped a hard spiral over the middle that somehow reached Harry among

three Golden Bear defenders for a 29-yard gain and a saving first down.

"He did it!" screamed KGO's Starkey.

The drive

was under way. Elway hit Mike Tolliver for 19 yards to the Cal 39. Next, with

31 seconds left, Mike Dotterer picked

up 21 yards on a surprise running play, a daring gamble that put Stanford on the Cal 18. Dotterer was held to no gain on the following play, but he did get the

ball close to the right hash mark, Harmon's

favorite area from which to kick. Harmon jogged in for the final field-goal

attempt. The crowd grew quiet. "Oh my goodness," gasped

Starkey as Harmon lined up for the kick with eight seconds to play. Bedlam

again. "It's good!" burbled Starkey of Harmon's field goal that

apparently had won the game for Stanford. "What

a finish for John Elway, to pull this out. This is one of the great finishes.

Only a miracle can save the Bears." True, all too true.

Hundreds of downcast Cal supporters started to make their way to the tunnels leading out of the

stadium. James Igoe, a San Francisco

attorney, was one of those who thought

the Bears were finished. "It was the biggest mistake of my life," he says. "I walked out on

history." Some Cal fans who departed early didn't learn about The

Play until they read about the game in the morning papers. Dick Hafner, Cal's

director of public information, told of one un fortunate Old Blue who sat

confounded through an entire dinner party after the game. "He couldn't

understand why everyone there was talking

as if Cal had won," says Hafner.

Stanford

made two critical mistakes on what seemed to be its winning play. Elway, standing next to Referee Charles Moffett, didn't let the clock run down far enough

before calling the time-out that preceded the field goal. Then, as

the kick passed between the uprights,

jubilant Stanford players ran onto the field to celebrate their dramatic

victory. This resulted in a 15-yard penalty

for having illegal players on the field. The penalty was assessed on the

ensuing kickoff, obliging Harmon

to kick from the 25-yard line instead of the 40. The penalty in no way

diminished Stanford's victory celebration.

It should have. Now Cal would have both a shorter distance to the goal

and more room to execute the Marx Brothers stunts that would get them there.

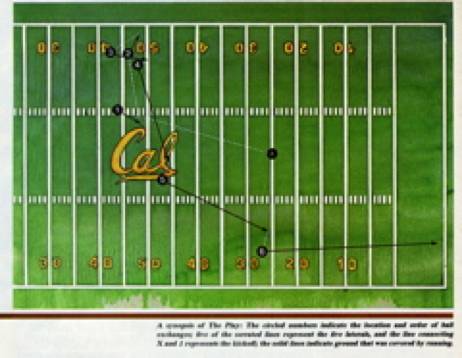

When the two teams lined up for the

kick, there was, as Cal

Special Teams Coach Charlie West said, "pandemonium everywhere."

Stanford was busily clearing the field of players who weren't supposed to be on

it. Cal didn't have enough. In expectation of a squib kick West had called for his onsides-return team, composed exclusively of

players accustomed to handling the ball. In the chaos, two members of the unit, defensive backs Gregg Beagle and Jimmy

Stewart, did not hear West call this

return formation and did not take the

field. So Cal lined up with only nine men, until West, responding

to frantic gestures from his players, sent in Running Back Scott Smith to take Beagle's place in the center of the

front line. Still more waves and shouts from the field. West was reluctant to act because, as he and Kapp agreed, in such situations "twelve men is a whole lot

worse than 10." A skinny 170-pound defensive back named Steve Dunn

was standing next to the perplexed coach.

"Let me go in," pleaded Dunn, who seldom played, even on

special teams. West hastily counted his forces—Kapp calls his special

teams "special forces"—and sent Dunn in just as Harmon approached

the ball.

Smith reached the field in time to fill the gap left by Beagle's absence,

but Stewart's position, second from the left on the front line, was unoccupied. This left Cal with only

four players in the restraining area between

the Stanford 35 and 40, not five, as

the rules stipulate. But this violation calls for only a correction by the officials before the

kick, not a penalty that would nullify the return. In the

confusion—players shuttling on and off the field, fans crowding the

sidelines—none of the six officials

noticed the oversight. Rodgers, captain of the special forces, was on the front line at the far left. Stewart's disappearance left a gap between him and

Smith. Linebacker Tim Lucas and

Cornerback Garey Williams were on the right side of this line. The

second line should have consisted of Tight End David Lewis, Moen, Running Back

Ron Story and Wide Receiver Howell, but Moen, for reasons unclear to West, was

playing five yards deeper.

"I noticed we were a man short," says Moen,

"so I decided to protect us farther back." It was one of those

inspired decisions by which history is

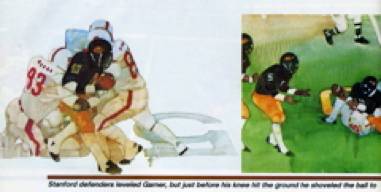

altered and football games are won. Garner was the intermediate return man and

Ford the deep man—deeper at

first than necessary, for he was not immediately aware that

Stanford was kicking from the 25. Dunn had gotten no more than five yards onto

the field when the ball was kicked, so in

effect he was playing no position at all. He would play it well.

The return formation may have been a hodgepodge, but the Bears did have a vague idea of what they

wanted to do, although at least two

of the principals, Moen and Ford, didn't

know what it was. Recalls Rodgers, "I saw our onsides team coming

on, so as. Mariet ran past me, I called out to him, `If you're tackled, lateral the ball.' Then I thought that's what we should do—just keep the ball alive.

Stanford might be expecting one or

even two laterals, but they wouldn't be looking for us to go crazy. I walked into the huddle and said, `Look,

if you're gonna get tackled, lateral the ball.' Everybody just looked at

me. 'I mean, don't fall with that ball.' That seemed to do it. Don't fall with

the ball."

It seemed a terrific, idea to young Garner. "I didn't know what we

were going to do," he says. "But Richard came into that huddle with a

very positive attitude. 'Don't fall with the ball.' I liked that. Why not? If

they're gonna beat us, we'll go out

fighting. Coach Kapp instilled that in us-100 percent for 60 minutes; never give in until the last second has ticked off.

We all held hands after Richard told us what to do. I knew then it wasn't

hopeless."

Moen wasn't so sure. "I wasn't in the huddle," he said.

"I was just walking around in the

middle of the field. I was mad and frustrated. I thought we'd played a

good game, good enough to win. I didn't have a lot of hope. I didn't know about

the lateraling. But I did have a weird feeling. I just wanted to see what was

going to happen."

Ford had

heard Rodgers yelling at him, "But I really couldn't hear what he was

saying. There was too much noise." And he was having troubles of his own.

"My legs started cramping up in the third quarter," he says.

"I'd expected it to be cold for the

game, so I'd worn tights under my uniform

to keep my legs warm. Then it turned up warm [57° at the kickoff], and it was

too late to take them off. I did a lot of

running in that game, and it finally caught up with me. At the start of

the fourth quarter I took off the tights. That seemed to help, but I could still feel the knots in my legs as I stood

standing there waiting for the kick."

Stanford

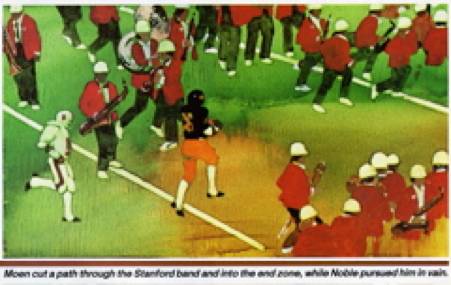

went for the squib kick because, according to Wiggin,

"That takes away the timing of the return." But not of this

one. The ball found the gap between Rodgers and Smith. Then it took a big hop

directly into Moen's hands. Had he been

playing in position, the ball would most likely have bounced over his

head into a virtual no man's land, where

Garner, the nearest player, would have had to track it down under pressure. Instead, Moen fielded the

ball cleanly at about the Cal 44. He

started running to his right "until I saw white

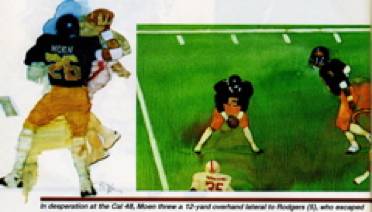

shirts"—primarily Stanford Strong Safety Barry Cromer's. On the Cal 48, Moen wheeled in front of

Cromer, spotted Rodgers perhaps 12 yards away near the left sideline, stopped and threw an overhand pass back to

him on the Cal 46. "I did it instinctively," says Moen.

"I thought Richard might have a

seam on the left side. I was a quarterback in high school, so I knew I

could get the ball to him. Then I ducked

past the Stanford tackler and started running toward Richard, circling so that I was behind him, just

to be there if he needed me."

Rodgers was startled to get the ball. "I saw Kevin looking around,

then the ball was in the air and I had it," says Rodgers. "I

started to run, but a Stanford man was in the way." This was Cornerback Darrell Grissum,

who would surely have tackled Rodgers the

moment he received the ball had not Dunn, trying somehow to get into the

action from his nowhere spot, rushed up and delivered a perfect block on Grissum near the sideline. Dunn's block enabled

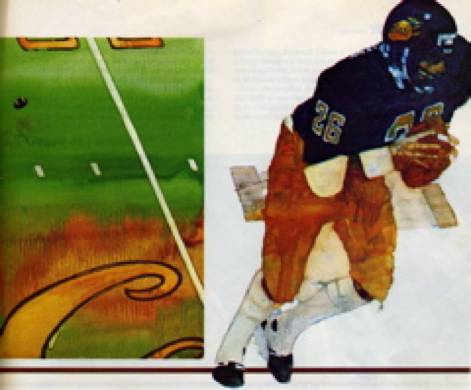

Rodgers to lateral to Garner on the Cal 43.

"When

Richard pitched it back to me, I made one fake and then attracted a crowd," says Garner, understating the case.

Stanford Linebacker David Wyman was the first to hit him, on the Cal 49.

Then Linebacker Mark Andrew joined in, and,

finally, what seemed to be the entire Stanford team. Harmon, the kicker,

leaped for joy when he saw Garner stopped. "I thought he was down,"

says Harmon. "Half of our guys were

going to the sidelines to celebrate." But there was no whistle, and Garner was resourceful.

"My knee never touched the

ground," he says. "They had my legs, but they were parallel to the

ground. My upper body was free. I could hear Richard calling to me, 'Dwight, the ball!' I shovel-passed it back to him, then I hit the ground. I

popped right back up to see if I could get another lateral."

At least nine players from

the Stanford bench charged onto the field at

that point in the mistaken belief that Garner had been stopped and the

game was over. Line Judge Gordon Riese

tossed his flag, charging Stanford with unsportsmanlike conduct. However, with the ball changing

hands so rapidly, in the eyes of fans and players from both teams the flag

could just as well have been against the Bears for something or other. From the south end zone the

Stanford band also rushed onto the

field, some members reaching as far as the 20-yard line.

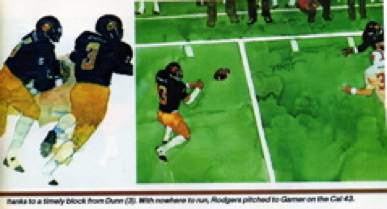

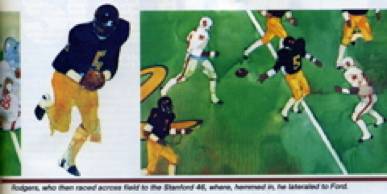

But Rodgers, running now with the

second lateral he'd received,

started upfield from the Cal 48, not quite knowing whom to dodge, because so many illegal players were on the field. Two of them, in fact, were Cal men,

Quarterback Gale Gilbert and Cornerback John Sullivan, both of whom took

one step onto the gridiron from opposite

ends of the Bears' bench when Garner

was hit. They stepped back undetected as

soon as they realized the ball was still in play. The most obvious of the

trespassers was Stanford's Tolliver, who had run perhaps 15 yards from the bench before he realized the game

wasn't over.

Rodgers reached the Stanford 46, where he was confronted by Cardinal Defensive Back 'Kevin

Baird. "The second Dwight got the ball to me," says Rodgers, "I

thought, 'Hey, we've got a chance.' I could

see that Kevin and Mariet were running alongside me and that the

Stanford man was in front of me. I acted

like an option quarterback, drawing that man to me. Then I lateraled into an

area, hoping that Kevin and Mariet wouldn't fight each other for the

ball."

Ford took this fourth lateral on the Stanford 47 and swung swiftly to his right, speeding by

players—legal and illegal—toward the startled Stanford

band. Tolliver, mean- while, had slipped and

fallen on his backside trying to get off the field. He was lying helplessly on the Stanford 34 when Ford

ran by him. "His entourage ran right over me," says Tolliver. "Sometimes I wonder why I didn't

just turn around and tackle that guy." Moen was directly behind

Ford. "I knew Kevin was close," says Ford, "but I didn't know

how close. I figured if I looked back, one

of the Stanford players would go for him."

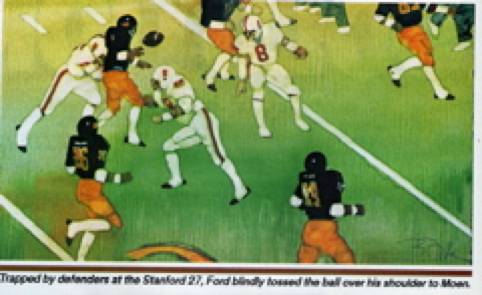

Ford was also grimly aware that

at any moment his legs might again cramp. At the Stanford 27, Ford was trapped

by three

Cardinal defenders—Outside Linebacker Tom Briehl, Safety Steve

Lemon and Harmon. "I just threw my body into all three of

them," says Ford. As his feet left the ground, he made a remarkable

over-the-shoulder toss—without looking back. "I didn't have much on

it," he says. "I wanted it to stay in the air as long as possible so Kevin could get to

it."

Ford's

dive carried him to the Stanford 24. It also flattened the three Cardinal

players and altered the course of three

others. Moen, racing under Ford's blind toss, actually overran it. He reached back for it at the 25, at

approximately the point from which

it had been released. Embittered Stanfordites later protested that this pass, though thrown back over

the shoulder, was still somehow forward. The films clearly show that the ball was thrown backward and that if Moen hadn't reached back for it, it would have hit

the turf at about the 27.

Ford's

climactic play removed virtually the entire Stanford team from the pursuit except Outside Linebacker Mike Noble,

who was behind Moen, and Grissum, who was in front of Moen as he received the

lateral. Howell took Grissum out with a block that was more of a shove. No flag

was dropped. The Stanford band, 144 strong,

was on the field by now. One bandsman, unaware that the game was being

lost behind him, stood facing the Cal

rooting section, waving his cap and

dancing in victory. The Axe committeemen were similarly rejoicing with the victory trophy on the Stanford 17-yard

line. Another member of the band frolicked near the goal line in a conehead. Most of the musicians, along with two

cheerleaders, were congregated between the goal line and the 15. Then, suddenly, Moen, in determined full flight, bore down upon them. Like a Red Sea they parted for

the miracle worker. "It was a

bizarre feeling," says Moen. "There

were so many people on the field, and I could see flags all over the place. And here I was running

right through the band."

"I was

following the play," says Referee Moffett, "and then I saw the band

running toward me. It was the damnedest

thing. Now I know how Custer felt."

Moffett admits he

didn't see Moen cross the goal line because the band was in the way. Kapp

didn't see the touchdown. Wiggin probably didn't, either. The only player

with a

reasonably unobstructed view of the proceedings was Noble, running in

futile pursuit of Moen through his own school band. "I didn't know what was going on,"

says Noble. "At

one point I may have had a shot at him, but it was a madhouse out there. Once I hit the band I slowed down. I didn't know where the end zone was, but I figured

the band must be in it."

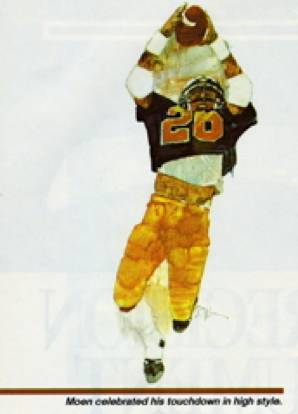

As Moen passed the goal line, he

brushed past saxophonist Scott DeBarger, a former high school football

player who later acknowledged he toyed with

the notion of trying to tackle the runner, a deed that would have thrown

what was already football's most improbable

play into even greater chaos. Moffett shudders to this day at the awful

prospect. "Imagine the confusion if

Moen had run into or tripped over or been tackled by a band

member," says Moffett. "Then we would have had to make a decision on

whether to award a touchdown." Fortunately, DeBarger's better instincts

prevailed. As it was, Moen bumped the sax

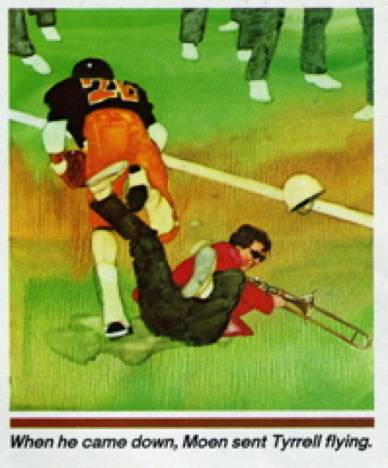

from DeBarger's grasp as he soared in

jubilation in the end zone. Gary Tyrrell, leader of the band's trombone section, was standing in the end zone playing the Stanford band's fight

song, All Right Now (the school's fight song is Come Join the

Band), when he looked up to see

Moen descending on him. "I had no

idea why a Cal football player should be in our end zone with the game over," says Tyrrell. "I was

apparently at the spot where he was

going to spike the ball. I barely had time to brace myself."

Moen landed on Tyrrell and sent him and

his trombone flying. Robert Stinnett, a photographer for the Oakland Tribune,

was standing next to the

musician at the time of the collision. His

on-the-spot photos of the occasion have been made into two posters that have taken their place among countless other artifacts of The Play. Stinnett's

pictures made Tyrrell as famous as Moen.

Moen said he never saw the trombone

player, so eager was he to celebrate the first touchdown of his college

career. Disengaging himself from Tyrrell, he pranced about the endzone with the ball held aloft. Then he had a

sobering thought: There were flags on

the field. Perhaps the highlight of

his athletic career would be wiped out by a penalty. "I finally

just sat down to await the verdict," says Moen. The officials had not

confirmed the touchdown, and the spectators, thoroughly drained, held their

reaction in check. The silence after so many

minutes of wild cheering was startlingly abrupt. The crowd had been transformed into a mute, befuddled

giant.

Starkey was now virtually speechless,

his baritone voice reduced to a grating

falsetto whisper. "The ball is still loose," he had shouted incredulously as The Play took form.

"He's going into the end zone!

There are flags on the field! The band's

on the field. . . ." Starkey once worked for Moen's father, Donne, in

the banking business in Southern California, and he had been concerned that he had scarcely mentioned the boy's name throughout the game. Now he was

maniacally screaming it into the microphone.

But something had to be wrong with a

play that "had four players throwing a total of five laterals, had illegal

players from both teams on the field and had

the Stanford band forming a corridor for the conclusion of a touchdown

run. Moffett, a Pac-10 official for 22

years, was indubitably the man on the

spot. As soon as Moen crossed the goal line, several Stanford assistant coaches confronted Moffett.

Wiggin, who had been taunted by a

finger-waving Cal nose guard, Bruce

Parker, was fuming on the sidelines. Moffett extended a restraining hand toward the coaches, players,

rooters and band members who were

crowding around him. He called his fellow officials into an on-field

conference.

"I assumed the

man had scored," says Moffett, "but I had to admit I lost him

in the band. I asked the other officials if he had crossed the goal line. They said he had. I asked if

anyone had blown a whistle during the

return. No one had. I asked if every

one of those laterals was clearly backward. They said they were. And the penalty flag? On Stanford for extra players and band on the field. Well then, I

said, we have a touchdown. I threw my hands in the air to signify as

much. And it was like starting World War III."

In fact, a cannon shot—the one

that accompanies all Cal touchdowns—was

fired, but this one was tantalizingly delayed. Igoe and those

others of little faith were outside the stadium

when, with disbelieving ears, they heard it. "I just stood there

for a second, a sick look on my face," says Igoe. "Then I started to rush back into the stadium with all the other

idiots. I don't know what I expected to see—an instant replay,

maybe."

Upstairs in the

broadcast booth, Starkey rallied for one final paroxysm: "The Bears have won. Oh my God, this is

the most amazing, sensational, heartrending, exciting, thrilling finish in the history of college football. I've

never seen any game like it in my

life. . . . The Stanford band just lost their team that ballgame. . . . This

place is like it's never been before.

It's indescribable here. . . . I guarantee you, if you watch college football for the rest of your life,

you'll never see one like this. . . ."

With thousands of

people now on the field, Moffett and the other officials broke into a perilous sprint for

their dressing quarters at the opposite end of the stadium. "Everyone was yelling at

us—players, coaches, fans, both bands," Moffett recalls.

"It was an alltime experience. Never in my wildest dreams had I

imagined that a game could end that way. This

one will be down in my memory book forever."

The officials'

locker room was scarcely a sanctuary. Within minutes, Wiggin, his

offensive coordinator, Ray Handley, and

Stanford Athletic Director Andy Geiger were bursting through the door demanding an explanation, insisting that they had photographic proof that an official had

waved the play dead when Garner was tackled. "They were in a state

of shock," says Cal Sports Information

Director John McCasey, who acted as a pool reporter in the

officials' room. "Paul was saying how

people's livelihoods depended on the officials' decisions." Moffett held his ground under the barrage. No whistle had been blown. Head Linesman Jack

Langley had been in perfect position

to call the play dead when Garner was tackled. "He was looking right

at it," says Moffett. "All

through that play I was saying to myself, 'Keep cool.' It was a weird situation, but we're trained to keep

our cool." The Stanford team,

meanwhile, sat fully dressed for 20 minutes after the -game,

waiting, as one member, Lemon, recalls, "for

something else to happen. We thought we would probably have to do

this play all over again. We sat there in total disbelief."

The

Pac-10 has no provisions for an official protest, so none was filed. The best Stanford could

do was persuade conference Executive Director

Wiles Hallock to issue a public

statement acknowledging that Cal had only four men in the restraining area on the fateful kickoff.

Hallock added, however, that it was a

violation that required no penalty. And, he said later, "I'm

pleased that in all the confusion, the officials never stopped

officiating." As for the play? "Well, it was just one of those marvelous things that happen in football."

Wiggin, his

opportunity for a bowl bid gone and his job and

those of his assistants in jeopardy,

remained inconsolable for months. "I'll take the criticism for not letting the clock run down

further on the field goal," he says

"but had the damn play been called correctly, it wouldn't have made any difference. Oh, it's very easy for some guy to sit in a bar and

say, 'That dumb-cluck coach.' Well, we'll

have a clock drill from now on. I'd just

like to put the whole thing behind me. It's

one of the most bizarre things I've

ever been a part of."

Elway, who

hit 25 of 39 passes for

330 yards and two touchdowns in the Big Game

and set an NCAA career record

of 774 completions and a Pac-10 record for yardage in a season (3,242), was as

enraged as his coach, and he is a young man not given to excessive emotion.

"These guys [the officials] ruined my last game as a college player," said Elway immediately after

the game. "This is a farce and a joke." More than a month

later, as he prepared to play in the East-West Shrine Game, Elway told Oakland Tribune reporter Ron Bergman, "I still feel the same

way about it now as I did in the locker room after the game. Maybe in time it'll wear off, but I'm still

bitter. Very bitter."

Harmon, the would-be hero of the game,

was no less disturbed. In two years at

Stanford he'd never been called on to kick

a "winner," and he had steeled himself for the opportunity all through the game. "I didn't care if

it had to be 70 yards," he says,

"I was going to be ready." He was, but his biggest moment had been

rendered meaningless. When the crowd had cleared, Harmon sat by himself

in the Memorial Stadium stands, trying

vainly to get a fix on what had happened. "It was a lucky play," he finally concluded. "I was

in a state of shock. I know I'll be

hearing about this for I don't know how long. But you've got to go on

with your life."

Noble

is haunted by his regrets. "Every time I look at a film of that play, I say to myself, 'There, right

there, I could've gotten him,' "

he says. "I still get hassled about it. I'll never hear the end of it as long as I live. But I guess you can

say I'm part of history."

Kapp's response

was predictable: "Hey, they had their party too soon. The game is 60

minutes, not 59 minutes and 56

seconds. This proved it."

The

Stanford band, a pariah even before the game to many fans and older alumni for its

iconoclastic halftime stunts and its insistence on an exclusively rock

repertoire at the expense

of traditional school songs, was attacked with renewed enthusiasm for its part in The Play. Mocked in the press

and bombarded with hate mail, the band retreated, as it were, into a

shell. "The band has served as a scapegoat

before," says Tyrrell, suddenly its most conspicuous member. "The hate mail was

not unexpected. Actually, we did get some nice thank-you letters from Cal alums."

Films of The Play exonerate

the band from serious wrongdoing. It had no

business on the field, of course,

but no Stanford defender was prevented from reaching Moen by any member of the band. Ford and

Howell basically eliminated all available

pursuers, and Noble, the only Cardinal player with a chance at Moen, ran unimpeded through the confused musicians.

Tyrrell himself

became a celebrity, interviewed on television and radio as frequently as any

of the four players. He also received offers from Cal alumni groups for his supposedly battered

trombone. Actually, the instrument wasn't even dented, and Tyrrell rejected all offers, preferring

to keep

it as a souvenir. Unable to acquire the real thing, the Berkeley Breakfast

Club, a booster group, presented Cal Athletic Director Dave Maggard with a plaque commemorating the great event, on which was

affixed a trombone that looked as if it had

been run over by a truck. This tortured horn might well prove as symbolic of the Big Game rivalry from here on in as the traditional Axe has been for

the better part of a century. The Axe, incidentally, was replaced in its

showcase on the Stanford campus by a giant screw.

Stanford did

achieve a measure of revenge the week after the game when reporters for The Stanford Daily published a bogus "extra"

edition of the Daily Californian, boldly

headlined NCAA AWARDS BIG GAME TO STANFORD. The prank paper was largely the work of undergraduates Tony Kelly, Mark Zeigler,

Adam Berns and Stanford Daily editor

Richard Klinger. However, the lead story, which began "The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has

awarded last Saturday's Big Game to Stanford, the Daily Californian was told late last

night," and a box containing a phony NCAA

rule by which an "injustice" may be corrected, were written for the

paper by Tom Mulvoy, a 40-year-old deputy managing editor of the Boston

Globe who was

attending Stanford on a journalism

fellowship. When a hesitant Klingler asked

Mulvoy if the staff should proceed with the spoof, Mulvoy advised him, "Go for it. If you don't you'll kick

yourself in 20 years."

Seven thousand copies of the ersatz issue were planted

in newsstands on the Berkeley campus before the real Daily Californian—fortuitously

late off the presses that day—could be distributed. "We stayed around to watch the

reaction," says Kelly, one of the Stanford Daily commandos who made the

early-morning trans-Bay trek from Palo Alto. "We heard a couple of screams of

'Oh no!' and a lot of swearing. One girl looked to be in tears. Marty Rabkin,

the Daily Cal's business manager, showed up. He picked

up an armload and was busy telling people the

paper was a phony, but Cal students

were walking by taking copies out of his arms the whole time. The look

on his face was hard to describe—disgust, maybe." At Stanford, says

Kelly, news of the hoax came "as a

catharsis. It helped alleviate the mood of despair on campus." Copies of the paper, as with most everything else connected with the event, have

become collector's items on

both campuses, and its authors have joined the expanding pantheon of

Play heroes.

The

biggest heroes—along with their satellite, Tyrrell—remain the mad lateralers. They achieved new

stature on a campus not noticeably appreciative of football stars and were greeted with ardent good humor as they

strolled across Berkeley's leafy glades. Alumni and businessmen in town hastened to entertain them with dinner and

drinks. Garner, working the cash register at a suburban Macy's store

over Christmas vacation, was often mobbed by customers. "I thought I was

going to get fired," he says. "Then when my boss found out who I was, he started talking to me about The Play. Turns out he was a Cal

alum."

The four

players were all good friends before, but The Play brought them even closer.

"When we see each other now,"

says Ford, "we all just burst out laughing." They are bound forever by a special experience, a second

set of Four Horsemen. "Now," says Garner, "we squeeze

each other's hands just a little tighter." END

©

Copyright 1983, Sports Illustrated