Marc Khoury

Our geometric intuition developed in our three-dimensional world often fails us in higher dimensions. Many properties of even simple objects, such as higher dimensional analogs of cubes and spheres, are very counterintuitive. Below we discuss just a few of these properties in an attempt to convey some of the weirdness of high dimensional space.

You may be used to using the word "circle" in two dimensions and "sphere" in three dimensions. However, in higher dimensions we generally just use the word sphere, or \(d\)-sphere when the dimension of the sphere is not clear from context. With this terminology, a circle is also called a 1-sphere, for a 1-dimensional sphere. A standard sphere in three dimensions is called a 2-sphere, and so on. This sometimes causes confusion, because a \(d\)-sphere is usually thought of as existing in \((d+1)\)-dimensional space. When we say \(d\)-sphere, the value of \(d\) refers to the dimension of the sphere locally on the object, not the dimension in which it lives. Similarly we'll often use the word cube for a square, a standard cube, and its higher dimensional analogues.

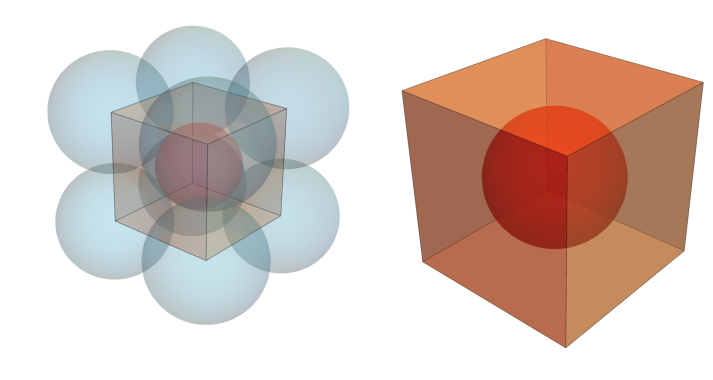

Consider a square with side length 1. At each corner of the square place a circle of radius \(1/2\), so that the circles cover the edges of the square. Then consider the circle centered at the center of the square that is just large enough to touch the circles at the corners of the square. In two dimensions it's clear that the inner circle is entirely contained in the square.

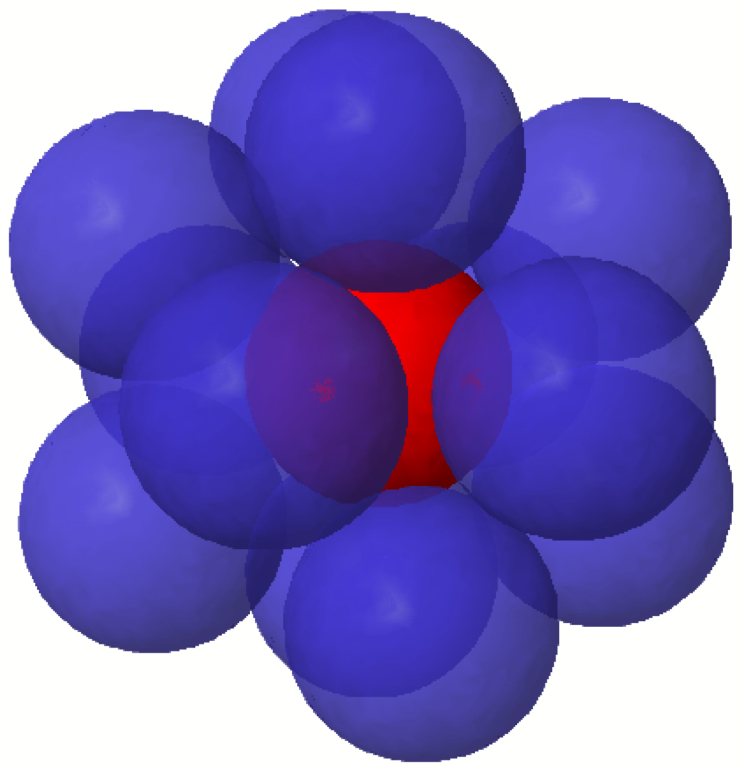

We can do the same thing in three dimensions. At each corner of the unit cube place a sphere of radius \(1/2\), again covering the edges of the cube. The sphere centered at the center of the cube and tangent to spheres at the corners of the cube is shown in red in Figure 2. Again we see that, in three dimensions, the inner sphere is entirely contained in the cube.

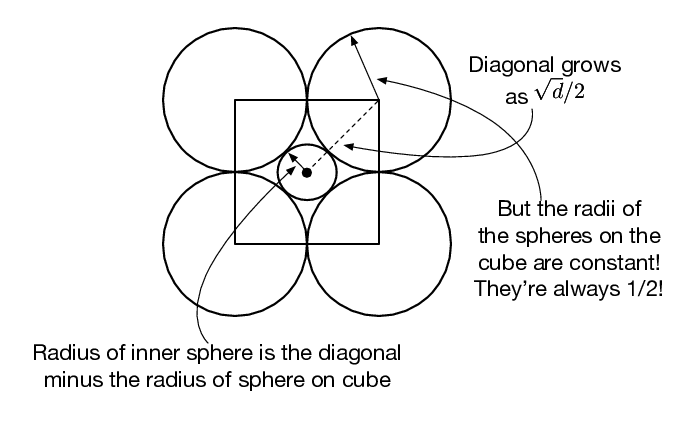

To understand what happens in higher dimensions we need to compute the radius of the inner sphere in terms of the dimension. The radius of the inner sphere is equal to the length of the diagonal of the cube minus the radius of the spheres at the corners. See Figure 3. The latter value is always \(1/2\), regardless of the dimension. We can compute the length of the diagonal as

\[ \begin{aligned} d\left(\left(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}, \ldots, \frac{1}{2}\right), \left(1,1, \ldots, 1\right)\right) &= \sqrt{\sum_{i = 1}^{d} \left(1 - \frac{1}{2}\right)^2}\\ &= \sqrt{d}/2 \end{aligned} \]Thus the radius of the inner sphere is \(\sqrt{d}/2 - 1/2\). Notice that the radius of the inner sphere is increasing with the dimension!

In dimensions two and three, the sphere is strictly inside the cube, as we've seen in the figures above. However in four dimensions something very interesting happens. The radius of the inner sphere is exactly \(1/2\), which is just large enough for the inner sphere to touch the sides of the cube! In five dimensions, the radius of the inner sphere is \(0.618034\), and the sphere starts poking outside of the cube! By ten dimensions, the radius is \(1.08114\) and the sphere is poking very far outside of the cube!

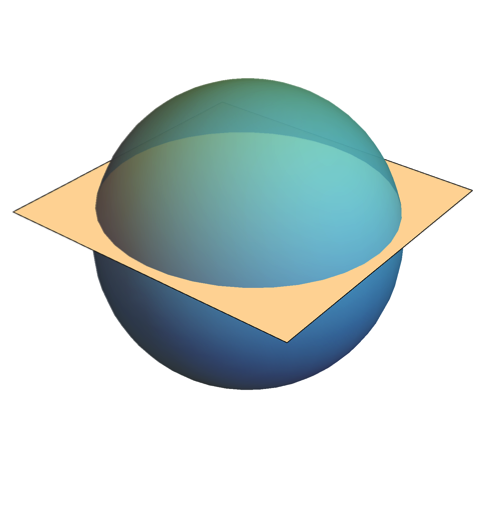

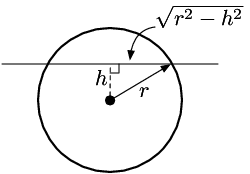

The area of a circle \(A(r) = \pi r^2\), where \(r\) is the radius. Given the equation for the area of a circle, we can compute the volume of a sphere by considering cross sections of the sphere. That is, we intersect the sphere with a plane at some height \(h\) above the center of the sphere.

The intersection between a sphere and a plane is a circle. If we look at the sphere from a side view, as shown in Figure 5, we see that the radius can be computed using the Pythagorean theorem (\(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\)). The radius of the circle is \(\sqrt{r^2 - h^2}\).

Summing up the area of each cross section from the bottom of the sphere to the top of the sphere gives the volume

\[ \begin{aligned} V(r) &= \int_{-r}^{r} A(\sqrt{r^2 - h^2})\; dh\\ &= \int_{-r}^{r} \pi \sqrt{r^2 - h^2}^2 \; dh\\ &= \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3. \end{aligned} \]Now that we know the volume of the \(2\)-sphere, we can compute the volume of the \(3\)-sphere in a similar way. The only difference is where before we used the equation for the area of a circle, we instead use the equation for the volume of the \(2\)-sphere. The general formula for the volume of a \(d\)-sphere is approximately

\[ \frac{\pi^{d/2}}{(d/2+1)!}r^d. \](Approximately because the denominator should be the Gamma function, but that's not important for understanding the intuition.)

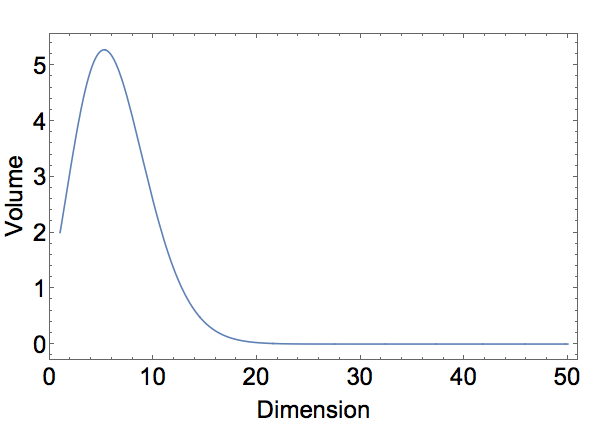

Set \(r = 1\) and consider the volume of the unit \(d\)-sphere as \(d\) increases. The plot of the volume is shown in Figure 6.

The volume of the unit \(d\)-sphere goes to 0 as \(d\) grows! A high dimensional unit sphere encloses almost no volume! The volume increases from dimensions one to five, but begins decreasing rapidly toward 0 after dimension six.

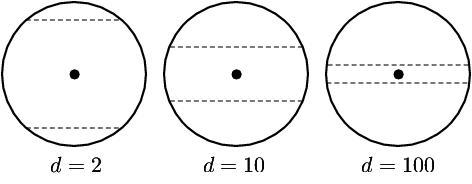

Given the rather unexpected properties of high dimensional cubes and spheres, I hope that you'll agree that the following are somewhat more accurate pictorial representations.

Notice that the corners of the cube are much further away from the center than are the sides. The \(d\)-sphere is drawn so that it contains almost no volume but still has radius 1. This image also suggests the next counterintuitive property of high dimensional spheres.

Suppose that you wanted to place a band around the equator of the unit sphere so that, say, 99% of the surface area of the sphere falls within that band. See Figure 8. How large do you think that band would have to be?

In two dimensions the width of the band needs to be pretty large, indeed nearly 2, to capture 99% of the perimeter of the unit circle. However as the dimension increases the width of the band needed to capture 99% of the surface area gets smaller. In very high dimensional space nearly all of the surface area of the sphere lies a very small distance away from the equator!

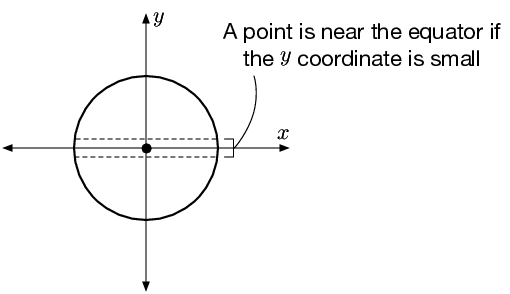

To provide some intuition consider the situation in two dimensions, as shown in Figure 10. For a point on the circle to be close to the equator, its \(y\)-coordinate must be small.

What happens to the values of the coordinates as the dimensions increases? Figure 11 is a plot of 20000 random points sampled uniformly from a \(d\)-sphere. As \(d\) increases the values become more and more concentrated around 0.

Recall that every point on a \(d\)-sphere must satisfy the equation \(x_1^2 + x_2^2 + \ldots + x_{d+1}^2 = 1\). Intuitively as \(d\) increases the number of terms in the sum increases, and each coordinate gets a smaller share of the single unit, on the average.

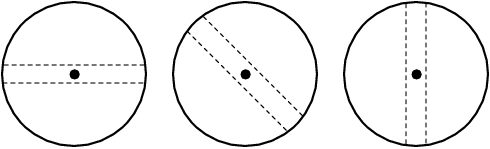

The really weird thing is that any choice of "equator" works! It must, since the sphere is, well, spherically symmetrical. We could have just as easily have chosen any of the options shown in Figure 12.

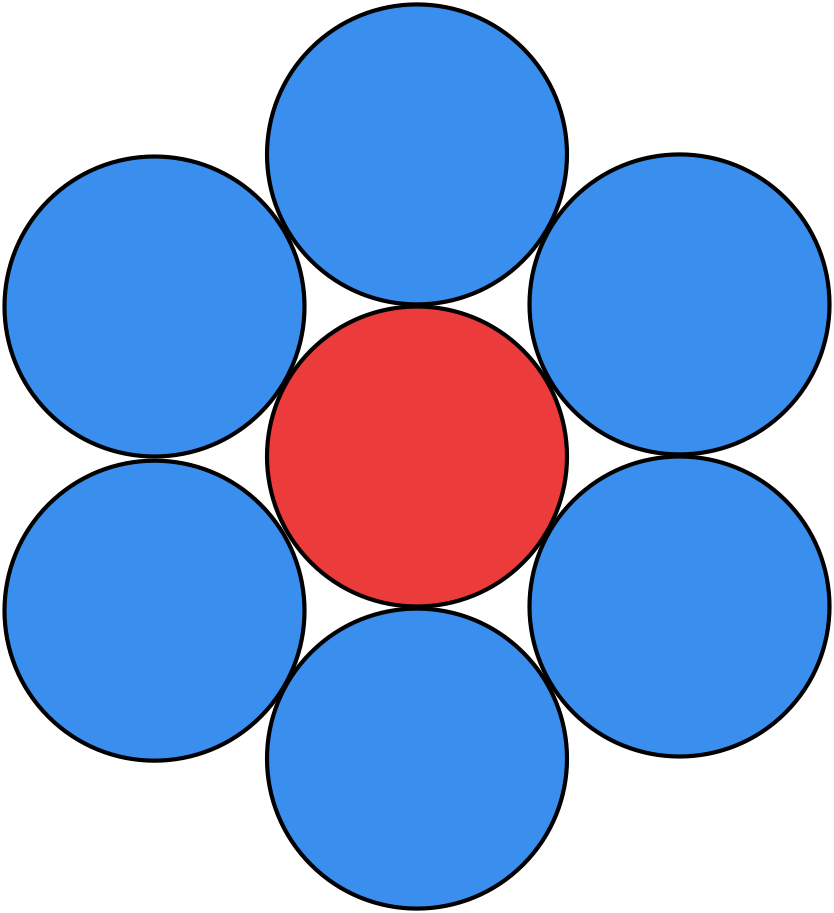

Consider a unit circle in the plane, shown in Figure 13 in red. The blue circle is said to kiss the red circle if it just barely touches the red circle. (Leave it to mathematicians to think that barely touching is a desirable property of a kiss.) The kissing number is the maximum number of non-overlapping blue circles that can simultaneously kiss the red circle.

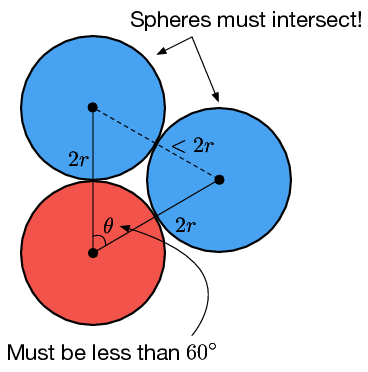

In two dimensions it's easy to see that the kissing number is 6. The entire proof is shown in Figure 14. The proof is by contradiction. Assume that more than six non-overlapping blue circles can simultaneously kiss the red circle. We draw the edges from the center of the red circle to the centers of the blue circles, as shown in Figure 14. The angles between these edges must sum to exactly \(360^\circ\). Since there are more than six angles, at least one must be less than \(60^\circ\). The resulting triangle, shown in Figure 14, is an isosceles triangle. The side opposite the angle that is less than \(60^\circ\) must be strictly shorter than the other two sides, which are \(2r\) in length. Thus the centers of the two circles must be closer than \(2r\) and the circles must overlap, which is a contradiction.

It is more difficult to see that in three dimensions the kissing number is 12. Indeed this was famously disputed between Isaac Newton, who correctly thought the kissing number was 12, and David Gregory, who thought it was 13. (Never bet against Newton.) Looking at the optimal configuration, it's easy to see why Gregory thought it might be possible to fit a 13th sphere in the space between the other 12. As the dimension increases there is suddenly even more space between neighboring spheres and the problem becomes even more difficult.

In fact, there are very few dimensions where we know the kissing number exactly. In most dimensions we only have an upper and lower bound on the kissing number, and these bounds can vary by as much as several thousand spheres!

| Dimension | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 6 | 6 |

| 3 | 12 | 12 |

| 4 | 24 | 24 |

| 5 | 40 | 44 |

| 6 | 72 | 78 |

| 7 | 126 | 134 |

| 8 | 240 | 240 |

| 9 | 306 | 364 |

| 10 | 500 | 554 |

| 11 | 582 | 870 |

| 12 | 840 | 1357 |

| 13 | 1154 | 2069 |

| 14 | 1606 | 3183 |

| 15 | 2564 | 4866 |

| 16 | 4320 | 7355 |

| 17 | 5346 | 11072 |

| 18 | 7398 | 16572 |

| 19 | 10668 | 24812 |

| 20 | 17400 | 36764 |

| 21 | 27720 | 54584 |

| 22 | 49896 | 82340 |

| 23 | 93150 | 124416 |

| 24 | 196560 | 196560 |

As shown in the table, we only know the kissing number exactly in dimensions one through four, eight, and twenty-four. The eight and twenty-four dimensional cases follow from special lattice structures that are known to give optimal packings. In eight dimensions the kissing number is 240, given by the \(E_8\) lattice. In twenty-four dimensions the kissing number is 196560, given by the Leech lattice. And not a single sphere more.