| HOME |

| PUBLICATIONS |

| Example Structures |

|

Other Materials |

| Biomimetic Millisystems

Lab |

| Why Folded Robots? |

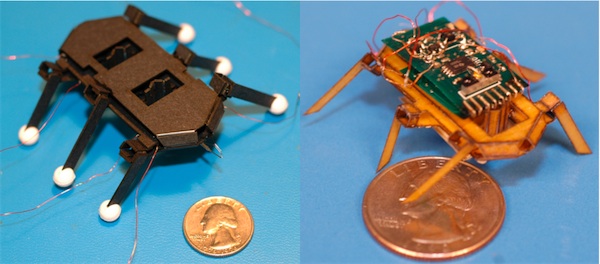

(left) 15 gram SMA driven robot, constructed from poster board [Hoover and Fearing, ICRA 2008] (right) 2.5 gram SMA driven robot with integrated electronics [Hoover, Steltz and Fearing, IROS 2008] As the size of a robot decreases, the ratio of its surface area to its volume increases. Because the mass of a robot is proportional to its volume, the increase in this ratio means that surface forces (electrostatic attraction, for example) become large compared to inertial forces. So, as robots (and machines in general) become smaller, friction in their moving parts can become a major source of energy loss, wear, and unpredictable behavior. In the Biomimetic Millisystems lab, we have developed a process called "Smart Composite Microstructures" (SCM) that enables us to build small, strong, lightweight, robots and structures whose ability to move comes from bending of compliant polymer hinges that connect rigid links made from carbon fiber and other composites. These structures are made as single flat pieces and are folded up to form more complicated shapes and linkages. They can also be integrated with smart actuators like piezoelectrics and shape memory alloy to provide motion.

|

| Prototyping Folded Robots |

|

Even with the SCM process, very small robots can be difficult to design and build. Their size makes assembly

challenging and the inherent difficulty of designing a 3 dimensional folded robot in a 2 dimensional drawing

also slows the process. To avoid costly errors in the early stages of design when many ideas will be tested

and discarded, we created a scaled analog to the SCM process using commonly available materials.

This scaled process lets the folded robot designer go from a design on paper to a functional scaled prototype

in as little as 20 minutes. Rapid iteration alleviates the risk of committing to a design and fabricating at the

small scale too soon. Instead, the designer is free to explore a variety of ideas at the larger scale,

discarding the unsuccessful attempts and rapidly integrating lessons learned in the process to produce a

design that is much more likely to succeed at the small scale. Fab Process Movie Movie of Crawler |

| The Prototyping Process: Step by Step Illustration with Hexapod Crawler Example | |

Required Equipment and Supplies

|

|

|

Step 1: The Drawing

The process begins with a 2 dimensional drawing in a program that supports vector graphics. In the lab we use the 2D CAD program, Solidworks. It is also possible to use a program like Corel Draw. However, Solidworks is preferred because it gives explicit control over dimensions and allows the user to define relations between entities within the drawing. Lines that will become flexure hinges in the robot are colored red while lines representing the outlines of the part are colored black. Blue lines are for squaring and scoring the workpiece. These lines are cut at different times - the reason for this is explained in the following steps |

| Step 2: Cutting the Flexures

The blue lines are first cut out to square the workpiece and create a fold line in the middle. The workpiece is folded and the flexure cuts are made, creating mirrored cuts in the workpiece shown in the picture to the right. |

|

|

Step 3: Flexure Layer Insertion

Glue is spread over the inner faces of the workpiece and a piece of polyester large enough to cover all flexure cuts is placed over one of the inner faces. (Alternatively, the posterboard can be prelaminated with hot mount film on the inner faces.) The workpiece is folded up, sandwiching the polyester film between the two sides. Care should be taken to align the flexure cuts. Alignment can be checked by holding the folded piece up to a light |

| Step 4: Laminating

The folded workpiece is passed through a hot laminator with maximum pressure exerted by the rollers. This step ensures even bonding of the posterboard to the polymer flexure film. The resulting sandwich is now ready to have the part outlines cut on the laser cutter. |

|

|

Step 5: Cutting the Outlines

The sandwich is placed back in the laser cutter. It is important to place the workpiece back in the same orientation as in Step 2 when the flexures were cut. The outlines of the parts are cut now. The picture to the left shows the parts with their outlines cut, but not removed from the workpiece. |

| Step 6: Releasing the Parts

The parts can now be popped out of the workpiece. The results are integrated, articulated parts with hinges where the flexure cut lines were placed in the drawing and rigid posterboard links between. |

|

|

Step 7: Pre-folding Linkages

If any of the parts contain linkages that can be folded before the parts are joined, they can be folded and glued at this point. In the picture on the left, fourbar linkages have been created by folding up the links attached to the two parts on the left. These fourbars will form the hips of a six-legged robot when the entire structure is assembled. The part on the right has been folded into a Sarrus linkage. This linkage sits in the middle of the finished robot and by contracting and expanding serves to lift and lower the two sets of three legs (tripods). |

| Step 8: Final Assembly

Individual parts or subassemblies can now be assembled. In the photo on the right, the three plates from Step 7 are glued together. The plate on the far left is on the bottom, the Sarrus linkage is in the middle, and the plate in the middle of the picture in Step 7 is on top. Legs have also be glued to the fourbar hips and the ends of the legs have been fitted with spherical silicone rubber feet. |

|

|

Example Structures |

|

|

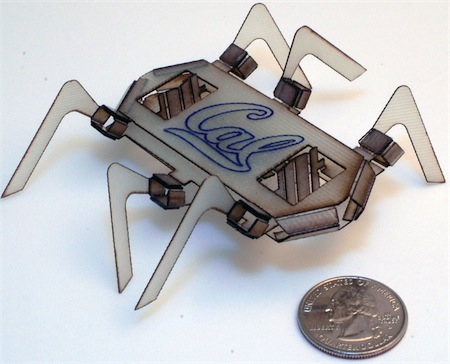

OpenRoACH Crawler

The OpenRoACH crawler is designed to use off-the-shelf components such as commercial gear box and CPU, and can be made with laser cutter and glue. design files on GitHub (with links to BoM and assembly photos) |

|

SMA Driven Crawler These are the files used to cut out the shape memory alloy driven crawler shown in the movie above. directions VersaLaser settings file (.las) body outline and cuts (.pdf) (.slddrw) (.dxf) (.jpg) straight legs (.slddrw) (.dxf) spider legs (.slddrw) (.dxf) Body with layers .slddrw |

|

Motor-Driven Hexapod

A DC motor can also be integrated with the crawler assembled in the step-by-step instructions. This crawler uses the same kinematics, but is modified to accommodate the motor and gear train. Flexure hinges can also be used as springs. In this prototype, a slightly bent knee is added to the leg to enable a small amount of compliance. |

|

5X Scale Mockup of Micromechanical Flying Insect

The

micromechanical flying insect uses two actuators per wing. Each

actuator drives a slider crank connected to a 4 bar. A pair of 4 bars

drives a spherical 4 bar which acts as the wing hinge. Each wing has 2

DOF and uses a 15 joint linkage. In total, the mockup uses 30 flexure

joints, and another 30 fixed joints for the structure/air frame.

|

|

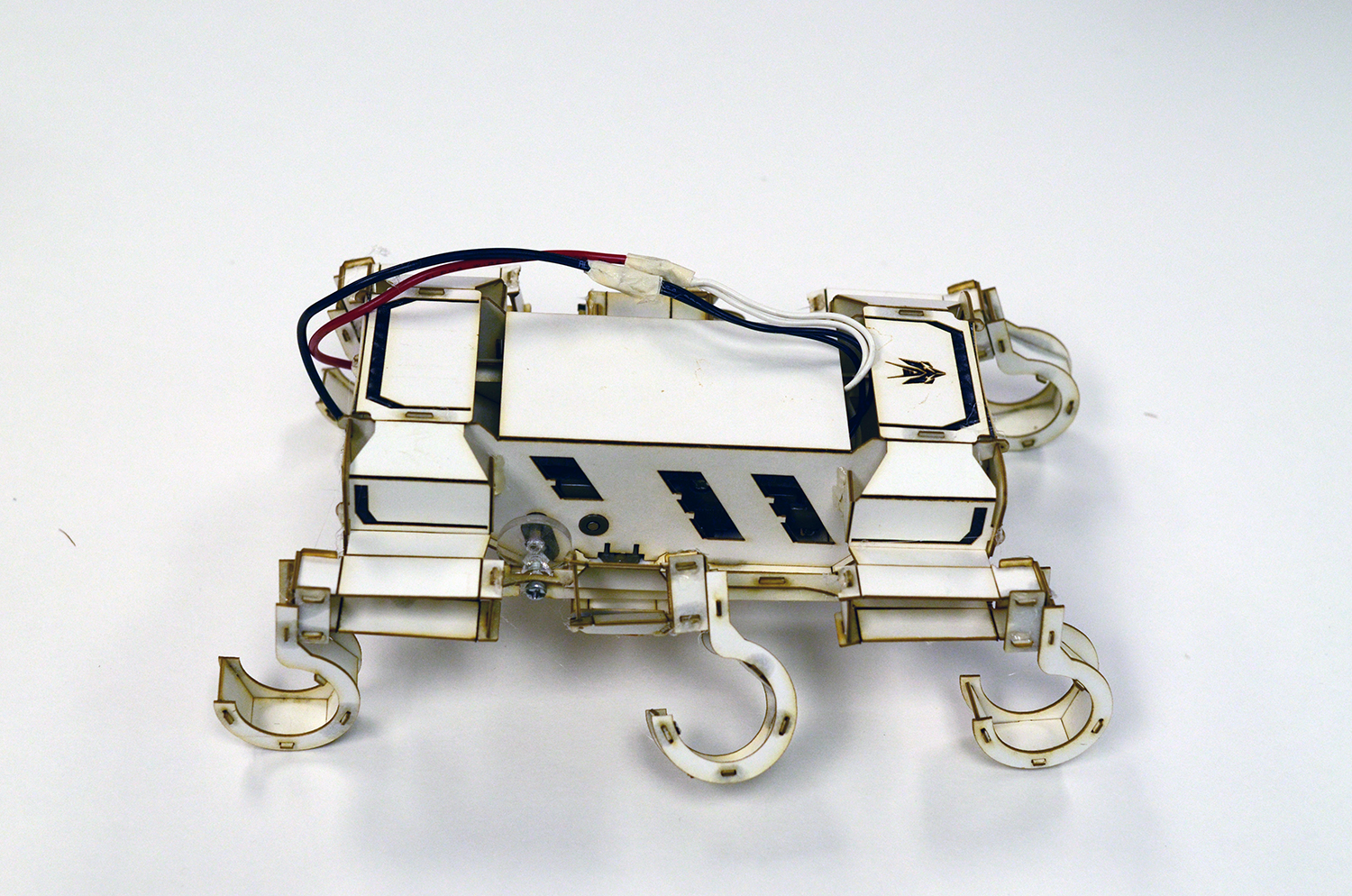

OctoRoACH robot

The

OctoRoACH robot design by A. Pullin

(Pullin et al. ICRA 2013).

OctoRoACH uses 1 DC motor per side. Transmissions can be found in small flying toys such as VAMP.

|

| Prototyping

using other Materials |

|

|

While posterboard is a convenient material that is readily available, inexpensive, and reasonably strong, for actuated models, a more robust engineering material is preferable. We have recently extended this process to use G10 fiberglass. the G10 provides a higher specific modulus than cardboard and is more robust when subjected to repeated actuation cycles. The use of fiberglass also opens the possibility of integrating printed circuit boards directly into the robot's skeleton. |

|

|

|

|

,

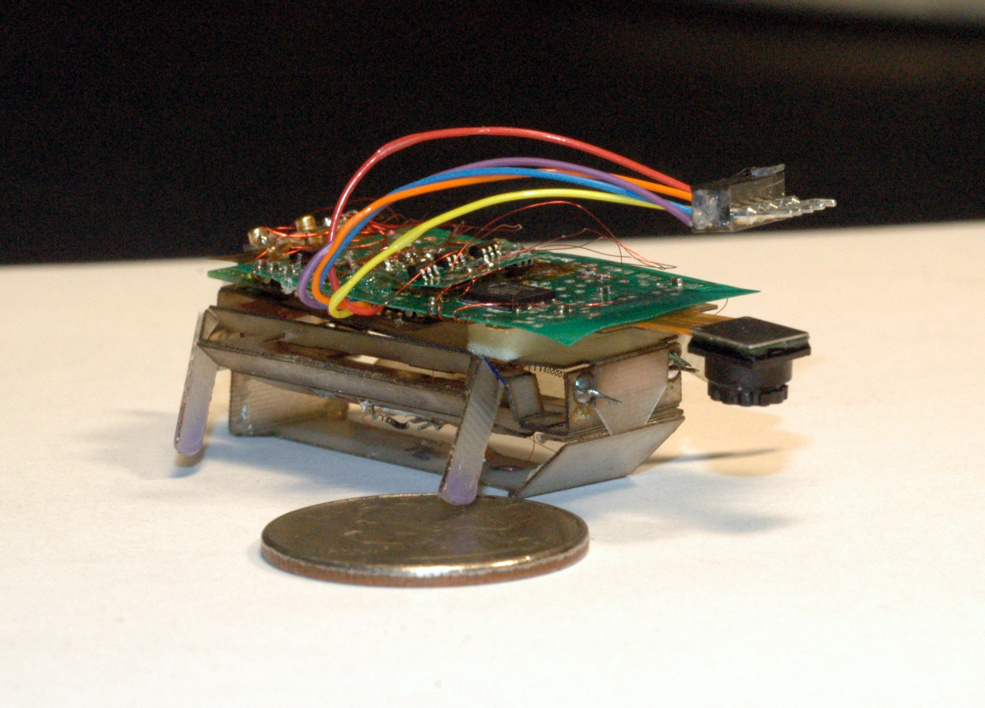

MEDIC Millirobot with

body-supported climbing

(Dec. 2010) The Medic robot is fabricated from thin fiberglass sheets, and has a mass of 5.5 grams, and is capable of positioning within 1 mm using static SMA drive. The robot includes camera and wireless. (Kohut et al. ICRA 2011.) |